[NASA/ESA/STScI]

This editorial was originally published in the Summer 2019 (vol. 48, no. 3) issue of Mercury magazine, an ASP members-only quarterly publication.

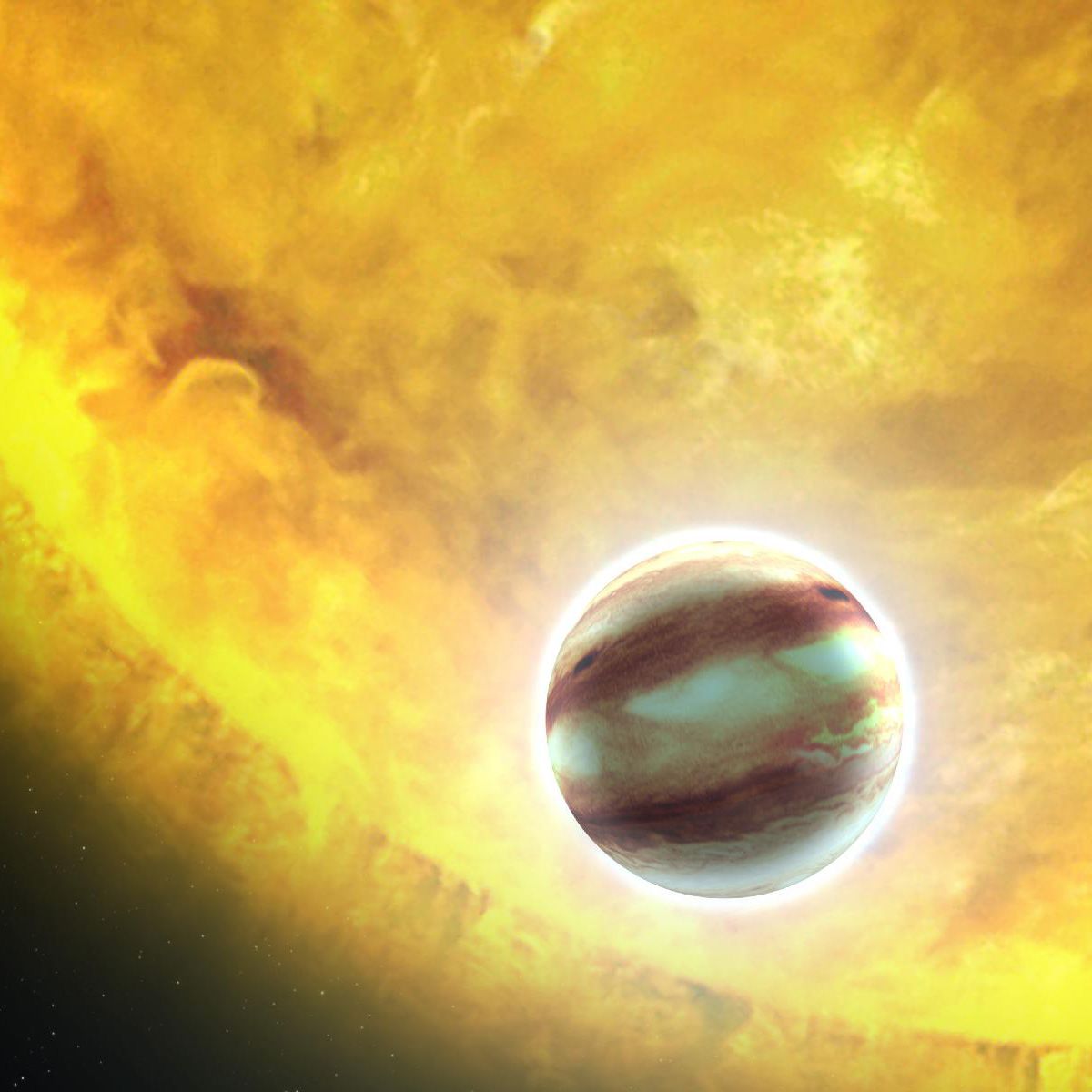

What do you call an orphaned moon with planetary ambitions? While this may sound odd, astronomers have identified a hypothetical type of object that could be hiding in exoplanetary data—and they suggest that we call these objects “ploonets.”

The ploonet hypothesis may appear, at first, to be a little outlandish, but the scenario is relatively straightforward. In a paper published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society last month, researchers have taken a stab at understanding what might happen to an exomoon in orbit around its host exoplanet as a star system evolves.

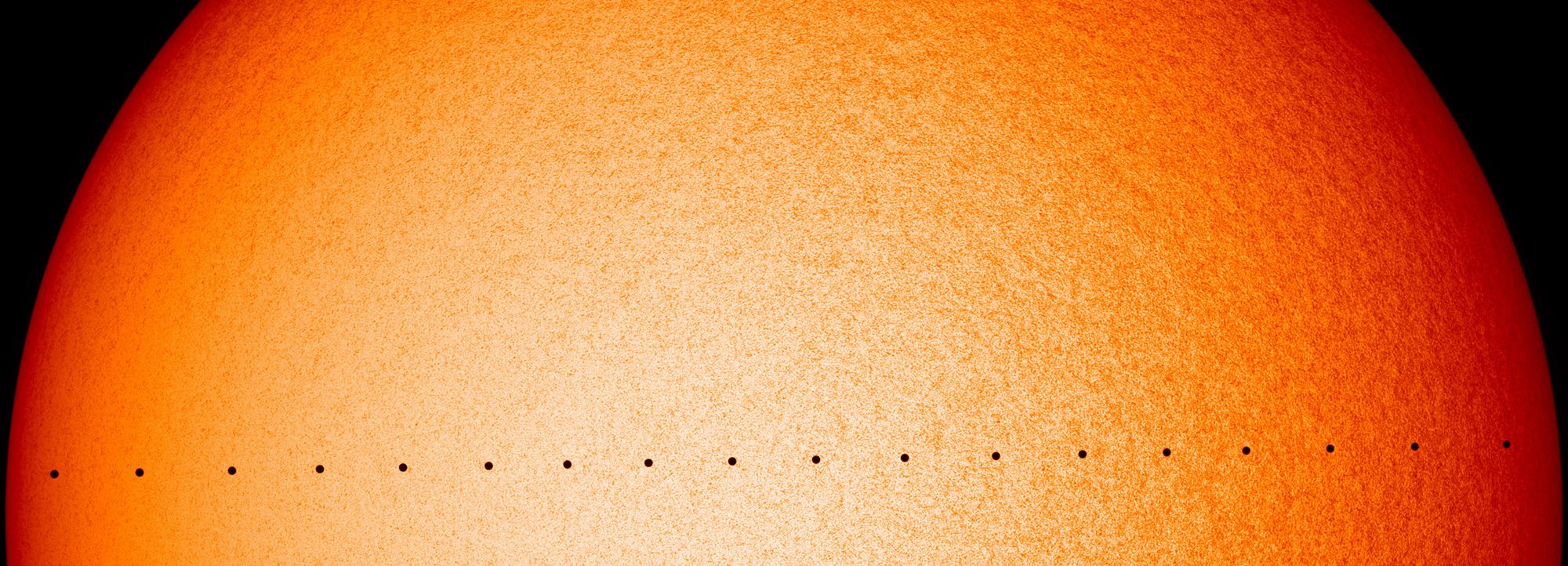

After forming in the cool outer reaches of a star system, a large gas giant exoplanet may have a bunch of large moons in tow. Over time, as the system evolves, the exoplanet may migrate closer to its star. This inward motion would cause some gravitational perturbations between the planet and moons, in some cases causing them to be ejected.

But what happens to them next? Well, after running their simulations, the researchers deduced that while 44 percent of the time the moons will smash into the planet, 48 percent of the time they will end up in orbit around their star sans planetary host (the remaining 6 percent will be eaten by the star and 2 percent will be slingshot into interstellar space). These newly independent ploonets try to live their best lives parading as planets and it’s possible that astronomers have already seen these objects.

This could also explain why astronomers have yet to discover any exomoons—of all the exoplanets discovered to date, most are “hot Jupiters” (i.e. large gas giant exoplanets that orbit close to their stars) and this class of world is most likely to lose its moons via this mechanism.

As an interesting side note, in the distant future, our very own Moon might have ploonetary aspirations: “Earth’s tidal strength is gradually pushing the Moon away from us at a rate of about 3 centimeters a year,” astronomer and lead author Mario Sucerquia told New Scientist. “Therefore, the Moon is indeed a potential ploonet once it reaches an unstable orbit.”

—

Dr. Ian O'Neill is the editor of Mercury magazine and Mercury Online. He is an astrophysicist, freelance science writer and science communicator. Read more articles by Ian.