This article was originally published in the Winter 2020 (vol. 49, no. 1) issue of Mercury magazine, an ASP members-only quarterly publication.

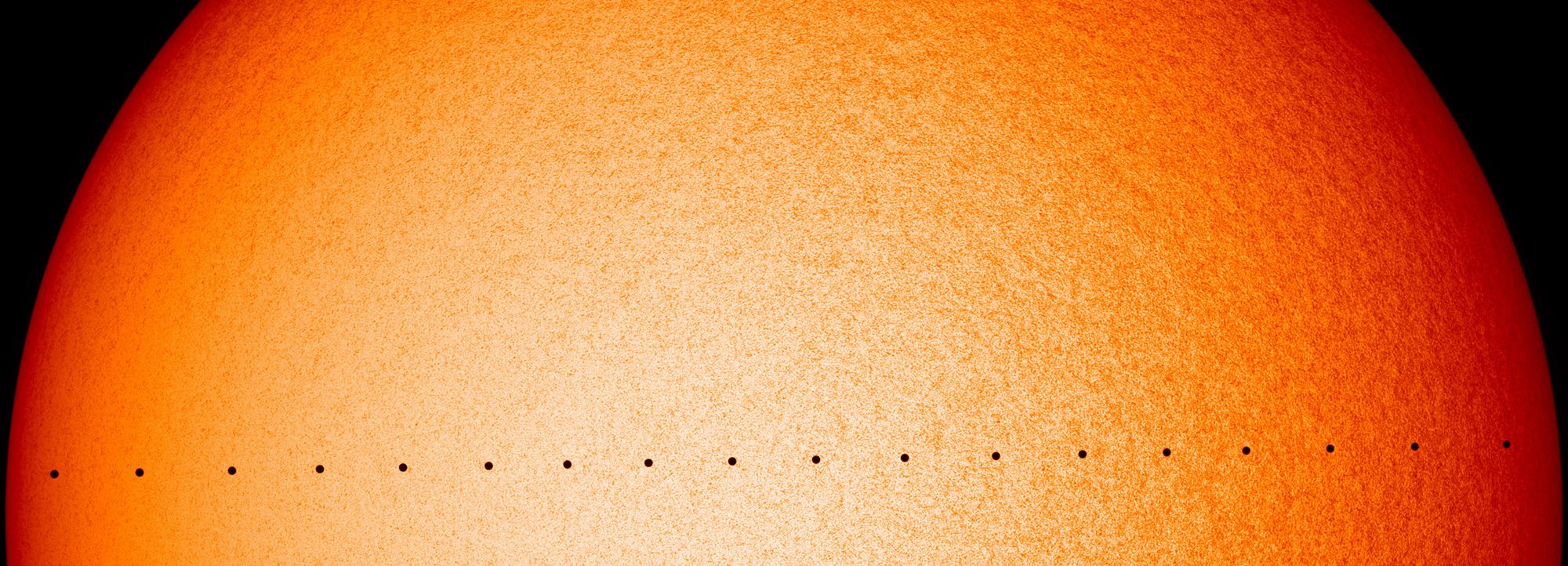

Image: Conjunctions are beautiful celestial events in the night sky, but in medieval Europe, they were viewed with superstition. [ESO/Y. Beletsky]

Planetary conjunctions are a striking sight in the sky, even now when no significance is attached to them. Centuries ago, however, they were infused with meaning, one of the most prominent being the conjunction between Jupiter and Saturn 675 years ago in 1345.

The 14th Century saw the peak of what became known as “conjunctionist astrology.” Great significance was attached to the planetary conjunctions of 1325, 1345, 1349, 1357, 1360, 1365 and 1373. Conjunctions of Jupiter and Saturn occur at 20-year intervals, accounting for those of 1325, 1345 and 1365. To understand astronomy of that period, one must deal with its ugly step-sister astrology, as it had ramifications far beyond mistaken belief. The 1325 conjunction, for example, prompted Dante to incorporate it in the Divine Comedy, the greatest of all literary works from the medieval period. He used the conjunction to bolster his prophecy of a great leader who would reform Christianity.

Even before it happened, the 1345 conjunction elicited a spate of publications across Europe. In England, John Ashenden took material from Arab sources to fashion a prognostication for the king of England. Edward III, he wrote, would enjoy victory over his enemies. In 1357, Ashenden felt compelled to write about the upcoming 1365 conjunction too, specifically attacking the “cruel and bestial” Scots, England’s chief enemy of the time. The linkage of Saturn-Jupiter conjunctions with English royalty had a long life: William Lilly linked the 1603 and 1623 conjunctions to the lives of James I and his son Charles I.

The most famous tract on the 1345 event was written in France by Gersonides, whose works in Hebrew were not translated into English until 1990. He states at the outset “that it is known by experience that a conjunction of Saturn with Jupiter signifies great and general events.” He noted that Mars would be joining these two planets in the same constellation, Aquarius. This portended “the destruction of a nation and a kingdom by a nation of a different religion.” More ominously he predicted “diseases and deaths which will last for a long time.”

According to calculations made by Donald Olson in 1990, Mars and Jupiter were in conjunction on March 1; Mars and Saturn were in conjunction on March 4; and the all-important Jupiter-Saturn conjunction took place March 21, 1345. But that was not all.

The French astronomer Johannes de Muris, who observed the solar eclipse of 1321, also wrote about 1345, noting that: “Before the conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter occurs there will be a very great eclipse.” This refers to a lunar eclipse on March 18. He goes on to presage that the position of Saturn during the eclipse means “the signification of this eclipse will be stronger with respect to human nature, causing lengthy sicknesses in some.”

Both prognostications indicated the events of 1345 would be felt for years to come, so the conjunction became the scapegoat for the greatest catastrophe Europe had ever experienced: The Black Death. Between 1347 and 1351, upwards of 25 million people died of the bubonic plague. Another outbreak of plague happened in 1373, the year of a Saturn-Mars conjunction; astrologers in 1373 reverted to the 1345 event to explain why the plague had returned.

The German scholar Henry of Langenstein wrote a treatise in 1368 in which he refuted the widespread belief that a comet in that year portended future events. The University of Paris, where he taught philosophy, was so impressed it encouraged him to write three more treatises critiquing astrology. The last of these, published in that plague year of 1373, dealt with planetary conjunctions, especially the one of 1345. Henry wrote there was no residual influence of the 1345 event in 1373, and denied any connection between it and the 1373 conjunction. However, he reluctantly admits that, since the influence of Saturn and Mars is maleficent, it could produce the 1373 pestilence, even without Jupiter. Finally, he insists that plague is due to many causes, superior (planets or stars) and inferior (terrestrial bodies).

If you want to see a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn, the wait is short, as there will be one on Dec. 21, 2020, when the planets will be only 6 arcminutes apart. As the closest such conjunction in centuries, it will be spectacular.

—

Dr. Clifford Cunningham is a Research Fellow at the University of Southern Queensland (Australia). He is Editor of the Historical and Cultural Astronomy book series published by Springer; and Associate Editor of the Journal of Astronomical History & Heritage. Since 1988 he has written or edited 15 books, including 7 asteroid books. Asteroid (4276) Clifford is named in his honor. Read more articles by Cliff.