This article was originally published in the Autumn 2021 (vol. 50, no. 4) issue of Mercury magazine, an ASP members-only quarterly publication.

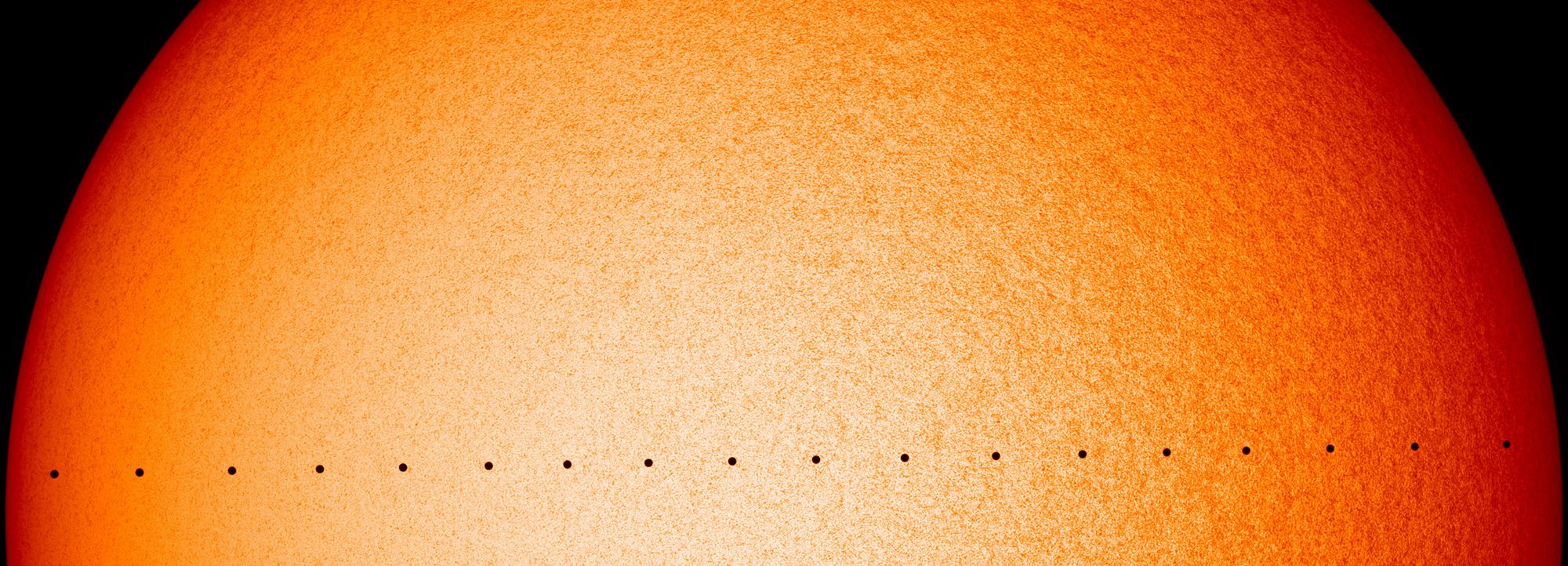

Image: Stephan’s Quintet is a galaxy group with five seemingly related galaxies, however that brighter bluer one is actually not related. [NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI]

The universe is a big place. We mean, a REALLY big place. You would think that with there being so much space in … space, everything would have plenty of room to move around and mind its own business. And yet, astronomers have found quite a number of interacting galaxies. In fact, if you look in the constellation of Pegasus, you can find five (well, really four, if you discount NGC 7320, which is a foreground galaxy) galaxies all coming together. Known as Stephan’s Quintet, it gives us a glimpse of a series of cosmic collisions that will ultimately result in one enormous elliptical galaxy millions of years from now. It’s amazing how the universe can take multiple separate galaxies, each with their own unique characteristics, and combine them to create one large galaxy.

If only it were that easy to combine students together into a cohesive team. Just put students near one another, add some gravity, and wait. Granted, perhaps if we had millions of years to do so, allowing near collisions and disruptions to occur until everything eventually calms down, that might work. But we don’t. We have a semester. Actually, we don’t even have a semester, because what we really need is for students to work well together after just a few short weeks of class, right? This is much better, pedagogically speaking, than expecting students to work by themselves during class, or, worse yet, sit there silently while we pontificate for an hour. But why?

According to Karrie Jones and Jennifer Jones’ application of cooperative learning, “the major benefits of cooperative learning at the college level fall into two categories: academic benefits and social-emotional benefits.” Cooperative learning provides students opportunities to wrestle with and conquer key concepts in class, while at the same time allowing them to work with others. This not only helps their peers understand the material better, but also allows students to vocalize and strengthen their own comprehension.

So how can we create student groups that merge naturally into a cohesive whole?

The easiest and most obvious solution may simply be to allow students to form temporary groups on an as-needed basis. “Turn to the person next to you and discuss the following question …” may be a straightforward way to encourage discussion in your classroom, and for simple activities, this may be sufficient. If you’re conducting more in-depth activities and tutorials, though, you may want to create something a little more permanent and more diverse.

Let’s face it, left to their own devices, students will tend to sit next to friends, and will therefore form partnerships with them. While some of those partnerships might be beneficial, there is a dark side. Barbara Oakley and colleagues found “a tightly knit group of friends is more likely to incline toward covering for one another rather than informing on infractions such as plagiarism or failure to participate in group efforts.”

Another problem with self-selected groups is that the eager and academically stronger students tend to sit toward the front of the room, while weaker students tend to congregate toward the back. “Groups containing all weak students are likely to flounder aimlessly or reinforce one another’s misconceptions,” says Oakley, et al., “while groups composed entirely of strong students often adopt a divide and conquer policy, parceling out and completing different parts of the assignment individually and putting the products together without discussion.”

How can you create a diverse group of students, each bringing their own strengths and perspectives to the table? While it might be possible to look at student GPA or ask about pre-requisite performance, in your standard Astro 101 course you don’t always have that option. But we do have Concept Inventory Surveys, each with its own acronym, such as the ADT (the Astronomy Diagnostic Test), the TOAST (Test of Astronomy Standards), SPCI (Star Properties Concept Inventory), the SSCI (Solar System Concept Inventory), and many others. Although these surveys are not designed to be indicators of learning ability, anecdotally we’ve found that the strongest learners tend to score within the top 10–15% while the weakest learners tend to fall within the bottom 10–15% on pre-course surveys, although not exclusively so. Distributing these students evenly among the groups usually ensures a good allocation of abilities, which will help to, as Oakley and colleagues suggest, “provide weak students with good modeling of effective learning approaches and perhaps tutoring from strong students, [and] provide strong students with the learning benefits that come from teaching others”.

If pre-course survey results were all that you consider, though, you may still run into problems. “Studies have shown that when members of at-risk minority groups are isolated in project teams, they tend either to adopt relatively passive roles within the team or are relegated to such roles, thereby losing many of the benefits of the team interactivity,” adds Oakley, et al. One such area where this comes in to play is gender, as discussed by Chija Skala and others in 2000. “Male personalities could overpower female personalities in the cooperative learning groups.” For this reason, we find it best to create groups that contain an equal or greater number of female members than male, or groups that are all male or all female. Other diversifying tactics can be employed to help everyone feel welcome to contribute to group discussions.

We also consider students’ fields of study when creating groups. Given the prevalence of math-phobia in Astro 101 classes, placing a business or computer science major in each group goes a long way to providing expertise on the quantitative aspects of the activities. At the same time, dividing up the art and music majors among the groups virtually guarantees that at least one member is inclined to look at problems from a unique perspective.

University experience is another category that you can look at. In addition to academic benefits, permanent groups can provide several social-emotional benefits. The first-year students in your class may find a built-in mentor in a seasoned junior or senior in their group (see our column in the Spring 2021 issue of Mercury for more details). One great by-product of using groups that are diverse in class year and major is that it tends to split up friends (but not always!).

“But what’s the problem with friends?” you might ask. Friends are already comfortable with one another, something that might seem advantageous. Unfortunately, friends within a group can form a “mini-bloc” that can dominate conversations and decisions, breeding resentment among other group members who aren’t insiders. Every semester, at least one friend group begs to be placed at the same table, and every semester, we have to explain our reasoning.

Once you’ve made the decision to create diverse groups of students with varying content knowledge, backgrounds, and interests, the question remains: How many students should be in a group? Common consensus appears to be that three to four students appears to be ideal to hold a good discussion. With only two students, there simply won’t be much rich discussion or a variety of ideas. With too many students, and you run the risk that one or more will drift off to the sidelines playing phone games. They will be the embodiment of the galaxy NGC 7320C, way off on the outskirts of Stephan’s Quintet, so far in the outskirts that it’s debatable whether it’s part of the grouping, watching everyone else collide and interact.

If every student attended every class, then three- to four-person groups would make sense. Realistically, though, students don’t always show up, particularly in classes with enrollments in the triple digits. On the odd Thursday, your perfectly diverse group of four might dwindle to a pair, or even a lone, isolated student. Padding each group with a couple of spare students helps ease the pressure. Admittedly, the groups might be a little heavy on the best days, but this still provides at least three or four students to tackle the activity on those odd Thursdays.

Simply by looking at Stephan’s Quintet, it’s hard to tell that the chaotic mess will eventually settle down into something that is both unified and stronger than any single member. The same goes for student groups. The first few meetings may be rocky, and disruptions may occur — ideally without any ejections — but given time, students, too, can settle down and form a unified, stronger unit.

—

C. Renee James is a science writer and professor of physics at Sam Houston State University, where she has taught introductory astronomy since 1999. She is the author of two books, “Seven Wonders of the Universe That You Probably Took for Granted” (2010) and “Science Unshackled” (2014), plus dozens of popular astronomy articles. Read more articles by Renee.

Scott T. Miller is a professor of physics and astronomy at Sam Houston State University, where he has taught introductory astronomy for non-science majors and engaged in astronomy education research since 2008. Read more articles by Scott.